Health

Research Reveals Neutrophils’ Internal Clock May Mitigate Heart Attack Damage

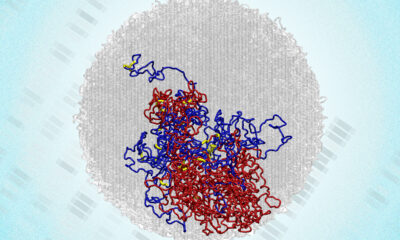

Heart attacks that occur at night tend to be less severe than those that happen during the day, according to a study led by researchers from the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) and Yale University School of Medicine. The findings indicate that the internal clock of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell, regulates their activity and consequently influences the extent of heart damage following an attack.

The international research team, headed by Dr. Andrés Hidalgo, discovered that inhibiting the fluctuations in neutrophil activity could prevent excessive tissue damage during daylight hours. This suggests that heightened neutrophil aggressiveness is linked to the increased severity of heart attacks in the early morning compared to those that occur at night.

In their study, published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, the researchers introduced a pharmacological strategy involving a drug named ATI2341. This compound effectively blocked the internal clock of neutrophils, maintaining them in a “nighttime” state and reducing their harmful potential during heart attacks. The drug targets a specific receptor on neutrophils, allowing the cells to remain less active, akin to their usual behavior at night.

Dr. Hidalgo explained that this therapeutic approach offers significant advantages over other methods that typically target neutrophil function or numbers, which can compromise the host’s ability to control infections or heal wounds. “Our study demonstrates that pharmacological delivery of a drug that activates a receptor on the surface of neutrophils induces their transition to a night-like, permissive state that alleviates the inflammatory response,” he stated.

The immune system naturally adapts to a diurnal rhythm, being more active during the day when exposure to pathogens is higher. However, this defensive response can sometimes lead to severe collateral damage, particularly in stressful situations such as myocardial infarction. Previous research has shown that nearly half of the damage inflicted on the heart following a heart attack can be attributed to neutrophils. This inflammatory damage varies throughout the day, indicating that circadian mechanisms may exist that limit neutrophil activity.

Neutrophils, while essential for fighting infections, can inadvertently harm nearby healthy cells due to their inflammatory response. The study emphasizes the dual nature of neutrophils: they protect against infections but can also exacerbate tissue damage. This is particularly relevant in cases of myocardial infarction, where excessive neutrophil activity can worsen outcomes.

The research team confirmed that lower neutrophil activity at night correlates with less severe heart attacks. They conducted experiments in which mice suffered greater cardiac tissue damage after a heart attack in the early morning, directly linked to increased neutrophil activity during that time.

In collaboration with the Multidisciplinary Translational Cardiovascular Research Group at CNIC, led by Dr. Héctor Bueno, the researchers analyzed data from thousands of patients at Hospital 12 de Octubre in Spain. Their findings reinforced the notion that timing plays a crucial role in neutrophil behavior and heart attack severity.

The team developed a strategy to effectively block the molecular clock in neutrophils, thereby reducing their harmful potential during heart attacks in mouse models. The compound mimics a factor produced mainly at night, tricking neutrophils into behaving as if it is nighttime, thus decreasing their toxic activity.

In experiments, treatment with the CXCR4 agonist, ATI2341, resulted in reduced myocardial tissue damage after a heart attack and helped preserve heart function in the following weeks. During their active daytime mode, neutrophils tend to accumulate around the edges of the injury, risking damage to healthy surrounding tissue. Conversely, in their nighttime mode, neutrophils cluster in the center of the wound, minimizing collateral damage.

Study co-author Alejandra Aroca-Crevillén highlighted the shift in cellular behavior as key to the observed protection. During the night, neutrophils effectively migrate to the damaged area while sparing healthy tissue. In daytime, their directional behavior diminishes, contributing to more extensive damage.

The study’s authors concluded that targeting the neutrophil clock could provide a straightforward and effective means to reduce the toxic activity of these cells during myocardial infarctions without hindering the body’s antimicrobial defenses. This groundbreaking research opens doors to new therapies based on chronobiology, potentially protecting the heart and other organs from inflammatory damage while preserving the immune system’s natural responses.

As the field of chronobiology continues to evolve, the implications of this study may significantly influence future treatment strategies for heart attacks and other inflammatory conditions, offering hope for improved patient outcomes without sacrificing the ability to fight infections.

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoUrgent Update: Tom Aspinall’s Vision Deteriorates After UFC 321

-

Science1 month ago

Science1 month agoUniversity of Hawaiʻi Joins $25.6M AI Project to Enhance Disaster Monitoring

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoMIT Scientists Uncover Surprising Genomic Loops During Cell Division

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoAI Disruption: AWS Faces Threat as Startups Shift Cloud Focus

-

Science2 months ago

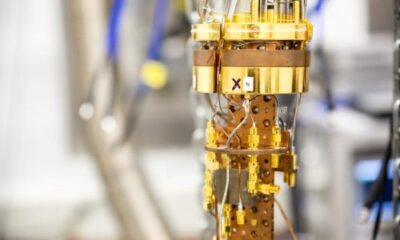

Science2 months agoTime Crystals Revolutionize Quantum Computing Potential

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoDiscover the Full Map of Pokémon Legends: Z-A’s Lumiose City

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoHoneywell Forecasts Record Business Jet Deliveries Over Next Decade

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoGOP Faces Backlash as Protests Surge Against Trump Policies

-

Politics2 months ago

Politics2 months agoJudge Signals Dismissal of Chelsea Housing Case Citing AI Flaws

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoParenthood Set to Depart Hulu: What Fans Need to Know

-

Sports2 months ago

Sports2 months agoYoshinobu Yamamoto Shines in Game 2, Leading Dodgers to Victory

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoMaine Insurers Cut Medicare Advantage Plans Amid Cost Pressures