Science

Researchers Achieve Lifelong Protein Control in Living Animals

Scientists have made a groundbreaking advancement by establishing a method that allows for the precise control of protein levels within living animals throughout their life span. This innovative technique enables researchers to adjust protein concentrations in various tissues, offering new insights into the molecular mechanisms of aging and disease. The findings were published in the journal Nature Communications on December 12, 2025, by a team from the Center for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona and the University of Cambridge.

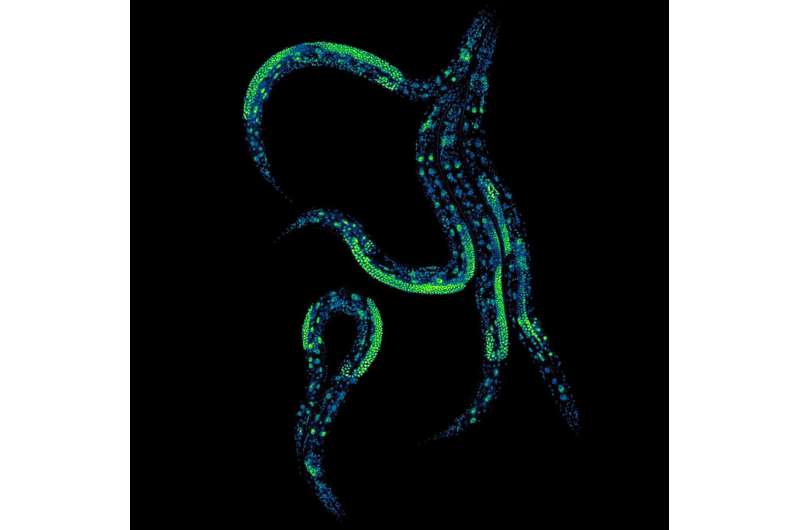

The research focused on the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, successfully demonstrating how scientists can manipulate protein levels in the organism’s intestines and neurons. This method opens the door for previously impossible experiments, such as identifying optimal protein levels for health maintenance and understanding how changes in one tissue can influence others across the organism.

Dr. Nicholas Stroustrup, a researcher at the Center for Genomic Regulation and senior author of the study, emphasized the significance of this approach. He stated, “No protein acts alone. Our new approach lets us study how multiple proteins in different tissues cooperate to control how the body functions and ages.” The technique’s ability to examine systemic processes like aging is particularly relevant, as it acknowledges the interactions between various organs that influence overall health.

Current methods often lack the precision needed to differentiate the effects of proteins across different body parts. Traditional on/off gene manipulation techniques do not provide the nuanced control required for detailed studies of aging and health. This new method allows scientists to finely tune protein levels, akin to adjusting the volume on a television.

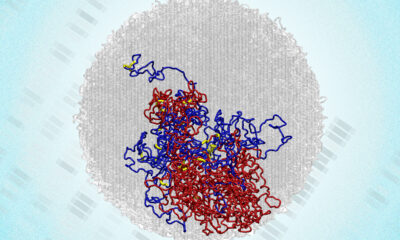

The innovation is based on an adaptation of existing technology derived from plant biology. Plants utilize a hormone known as auxin to regulate growth. Previous research with yeast led to the development of the auxin-inducible degron system, or AID system. This system works by tagging proteins with a degron, which an enzyme called TIR1 recognizes to degrade the protein, but only in the presence of auxin. When the hormone is removed, the protein returns.

The research team enhanced this system by engineering various versions of the TIR1 enzyme and degrons, testing them across over one hundred thousand nematodes. The result is a more flexible version called the “dual-channel” AID system. This system allows for precise control over protein levels, determining not only when but also where in the body these changes occur.

The key innovation involves genetically engineering worms to produce TIR1 enzymes in specific tissues. When these worms consume food containing auxin, the hormone activates TIR1, which then removes the appropriate amount of the tagged protein. By employing two different TIR1 enzymes, each responding to different auxin compounds, researchers can independently manage the same protein in various tissues, such as the intestine and neurons. This control extends even to reproductive cells, a significant hurdle previously encountered with AID systems.

Dr. Jeremy Vicencio, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Genomic Regulation and co-author of the study, remarked on the engineering challenges faced in developing this system. He stated, “Getting this to work was quite an engineering challenge. We had to test different combinations of synthetic switches to find the perfect pair that didn’t interfere with one another. Now that we’ve cracked it, we can control two separate proteins simultaneously with incredible precision.”

The implications of this research are vast, offering unprecedented opportunities for biologists to explore the intricacies of protein interactions and their effects on health and aging. As the scientific community continues to investigate these new possibilities, the dual-channel AID system stands as a significant advancement in the field of molecular biology.

For further details, the findings are documented in Nature Communications under the DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-66347-x.

-

Top Stories1 month ago

Top Stories1 month agoUrgent Update: Tom Aspinall’s Vision Deteriorates After UFC 321

-

Science1 month ago

Science1 month agoUniversity of Hawaiʻi Joins $25.6M AI Project to Enhance Disaster Monitoring

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoMIT Scientists Uncover Surprising Genomic Loops During Cell Division

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoAI Disruption: AWS Faces Threat as Startups Shift Cloud Focus

-

Science2 months ago

Science2 months agoTime Crystals Revolutionize Quantum Computing Potential

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoDiscover the Full Map of Pokémon Legends: Z-A’s Lumiose City

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoParenthood Set to Depart Hulu: What Fans Need to Know

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoGOP Faces Backlash as Protests Surge Against Trump Policies

-

Politics2 months ago

Politics2 months agoJudge Signals Dismissal of Chelsea Housing Case Citing AI Flaws

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoHoneywell Forecasts Record Business Jet Deliveries Over Next Decade

-

Sports2 months ago

Sports2 months agoYoshinobu Yamamoto Shines in Game 2, Leading Dodgers to Victory

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoMaine Insurers Cut Medicare Advantage Plans Amid Cost Pressures